Where do you want your picture taken?

A poem by Lorna Crozier

They lived here when they were beautiful,

though they didn’t know it then: one, a girl named Nellie,

rough hands smelling of horse and sunlight,

arms and legs brown as caragana sticks.

Her mother in an apron stood on a small rise,

staring into the dusk draped with smoke to see if the fire

that ravaged the neighbour’s field would shift to the west

or climb the hill and fall

upon the farmhouse where her children waited and watched

her long, straight body turned away from them, darkening

in the setting sun. Nellie said to herself,

"What a lonely figure.”

It startled her—that thought—her mother, rarely alone,

a husband to care for, five kids to raise.

Years after her mother’s death,

after the death of her own husband,

Nellie will live in Saskatoon in a home called Sunset.

In a store-bought dress,

the toes of her pantyhose visible

in white sandals with a decent heel,

she will tell the photographer,

“Those pioneers were carried on the backs of women.”

The children, too, were pioneers, though it’s older people

in dusty wool we think of when we hear that word,

not the six Wilcox kids who each had to pump a hundred strokes

to fill the trough before they went to school,

their mother finishing the job, the geldings pushing at the gate.

Not eleven-year-old Olesa Guttormson and her sister

who got up at 5 a.m. to wash

the office and rooms at the Watson Hotel.

“We didn’t get very much school because we didn’t go to school. We worked.”

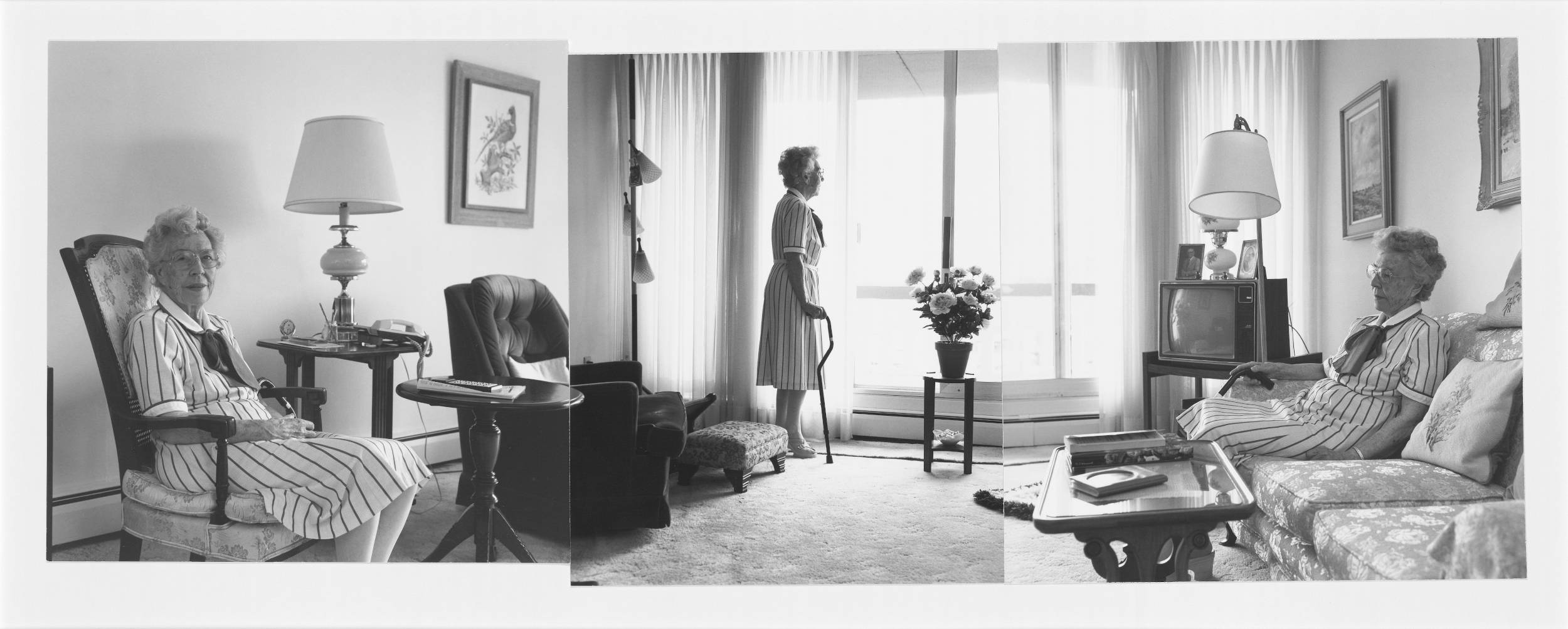

In the photograph, Olesa sits in her wheelchair,

feet swollen in cloth slippers. Most beautiful,

she holds a harmonica to her lips.

The picture’s titled: “Olesa Loves Music.”

My own mother, seldom photographed, was kept from grade one

so she could clean the outhouse, wash the floors, bake loaf after loaf

of bread at the neighbours’ farm.

Too short to pound the dough on the kitchen table, she stood

on a milking stool.

She milked, too.

Most beautiful she was

in the snapshot I keep on my desk. On her eightieth birthday

her friends threw her in the outdoor pool, her eyes

bluer

than the water. They carried that colour and shine

for eight more years before I had to close them, kissing each eyelid

and then both temples where they dipped just above the cheekbones

as if a thumb had pressed there when the clay was wet.

On the farmsteads that branched off the grid,

sheds, coops, and granaries settled in the grass

when there was grass, in the dust

when there was not.

Sometimes the barn was part of the house—in bed, half asleep, you could hear

the milk cow shifting in the straw, smell the urine and manure,

hear the sow’s deep sigh as she

settled into sleep, the warm sound of the piglets’ sucking—

or the barn was its own building big as a wooden ship

turned upside down for repairs,

two houses could easily fit inside it.

No trees at first, then

a shelterbelt planted on three sides,

caraganas, elms, sometimes spruce.

There was a well and a pump. A trough,

an iron plow, wagon wheels. There were shattered

whiskey bottles, leather harnesses, a wooden laundry tub,

the bleached bones of cows by the slough,

a dirt road the feet remember, long before gravel,

the soft sound the earth made beneath them.

When it rained the road turned to gumbo. You couldn’t drive it

with a horse and wagon, just a horse, its big hooves sinking in and

sucking up the mud

like rubber plungers. Each farm was plotted on a map,

its site and township. Yet passing through, you’d swear they were

the same farm,

the villages, too, though the people differed

in their countries of origin, their family names—little else

to claim.

Hail that shattered the south windows

made a U-turn in the wind and hours later

broke the windows to the north. You’ll hear this story

in a dozen places. The dates change

but the damage done remains the same.

Everyone lost, everyone struggled

though many said they were never hungry, never cold.

It was a woman’s lot

to marry and have children, to bury those she loved and keep on going,

“always something, a kettle of soup—

something hot on the stove.”

Once there was a high school, once a blacksmith’s shop, once a café,

once a town hall,

once the mail came here, crossing open country and an ocean,

then thousands of miles again. Did a letter from Norway arrive, from

Devonshire, from China?

Were there any kin left to send one?

Three brothers killed during the revolution, a sister dead

from typhoid fever.

Imagine a letter from Nabor, Southern Russia, following the trail

of the family who’d escaped, who’d settled in a town

with a postmistress, a store, the beginning

of a school. No matter what it said,

they’d have saved the letter, placed it perhaps

beside the samovar, the small blue vase,

what they’d brought to Saskatchewan in 1923.

In her room at the home called Sunset, Anna at eighty-five

poses with such a samovar. The length of her torso, it dominates

the chrome table covered with a lace cloth, plastic laid on top to keep

the lace clean.

When asked where

she’d like to be photographed, she wants to go back

to the home place where no one lives anymore.

Small but not insignificant, not out of place

she stands in front of the wind-scoured house

Clutching a shawl in one hand, a cane in the other, she isn’t smiling,

but gazes past the photographer, chin slightly lifted,

the wood in the siding and the door close behind her

give off the silver gleam of daguerreotypes, her face, too,

has that strange shining, the expression hard to read.

This is where you stand when you are old.

It must be a cool day, but not too cold.

Her hands and head bare,

she is fully in her body in this place

another would call desolate; another, sad.

This is the picture she wants us to see.

There was a family, feet running up

the three steps to the door.

There were animals

they killed to eat.

There was a cat who hid its kittens.

Stubble crackled like small fires beneath their shoes

as they ran across it.

This is what her look says,

This is what her look says,

this is what it makes us witness:

what never leaves the world is loss.

Where would I want my picture taken?

The windmill is more accurate than a clock.

Look how fast its blades spin.

Ida Hogel says she can’t believe it. “My oldest girl is 71.

How old am I? I must be going backward.

I must be 49!” And she laughs. She laughs

as the strong wind pushes her backwards

down the road she’s travelled

but now what’s ahead is a darkening

that is not yet dark,

something that’s seen

only in that narrow space between

the sun’s last shining and its going down,

the shutter open, then clicking shut.

Ida wears a wristwatch, easily read, on the cuff of her blouse

as if, at any moment, she might be called upon

to take a pulse.

In this country wind feeds the quickness of things.

Fire eating the grass,

a barn’s lean, the fading of names painted

on storefronts, on a wooden cross, on grain elevators:

wind hastens the ageing of the face and hands.

Off Highway 41 there is a village called All Things Pass, and a village

called Bewildered, and a village called Time Blows Through.

They are the same village and they are different.

Who, you wonder, used to look out those windows?

Long ago a woman watched for a car to drive up the road

with its tail of dust,

longer ago, a horse and buggy,

longer ago, the shape of a tired man, walking.

There was a dress a woman wore when she cooked and cleaned,

when she plucked the chickens. It was called a house dress.

Usually it had buttons down the front and a print that faded

with each wash.

The other dress she wore to a church service or a wedding, the same

one to a funeral. Sometimes there was enough to buy the end of a bolt

of cotton to make a dress for a dance. There was a time when all she

wanted was to touch

her husband. She wanted him to touch her, too.

You’d be frightened now if you saw a face behind that window,

looking out.

You’d have to make a bargain with the wind so it would help

the ghost pass over.

In knee-high grass in the black and white of the photograph

Grace stares at wild flowers and seed-heads in her hand,

the straps of her black purse hooked over one wrist, her coat

unbuttoned. She looks like

the kind of woman who would have excellent

penmanship, a woman who’d know what jewellery to wear

to what occasion. Like Anna, the place she has chosen

is the old homestead, this time a three-story house with perfect

posture, every board intact, keeping the rain away

from the nothing-there

inside. What is strange

is the stillness, the grass that surrounds her doesn’t move

though you know in the world

outside the frame the stems are swaying and the seeds are blowing away.

The photographer, almost seventy, could have been

daughter to the women from the Sunset Home.

Though she never shirked

she’d have liked life

to be sweeter. You can hear that in the titles:

“Memories Come Flooding Back,”

“Strength in Friendship,”

“Thankfulness.”

“No Generation Gap.”

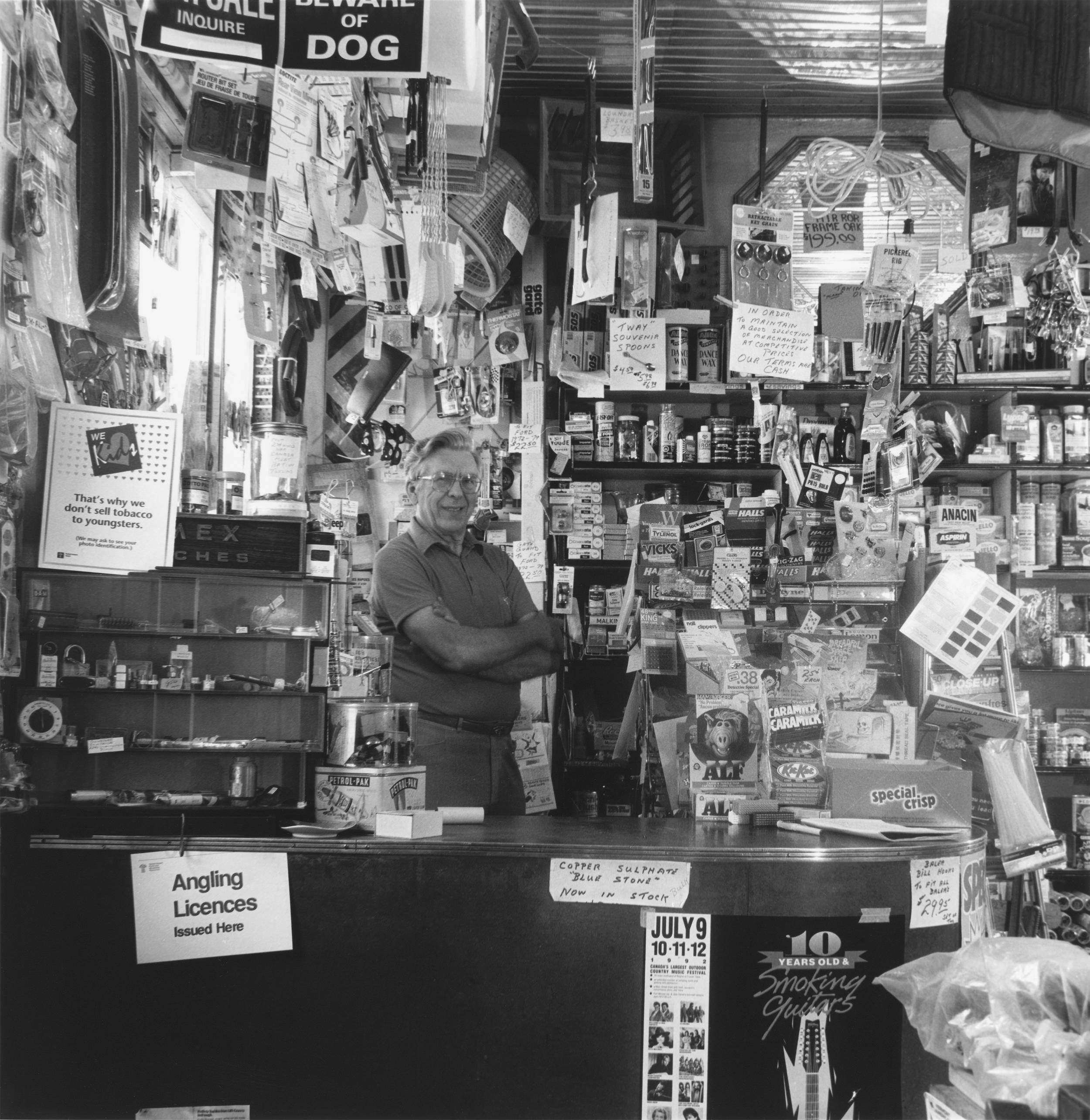

In every village there is a hardware store.

Glue, hammers, egg beaters, salve for horses, Epsom salts,

nails, fly ribbons, paraffin, wooden clothespins, all the small

necessities of daily tasks.

High above the counter, hangs a sign for sale: “of dog”;

the camera has cut off the top line.

You love this accident, or is it mischief?

The missing word bears witness to

what else is missing.

The owner stands behind the counter.

He is smiling. Time and light are running out.

Beware.

Once I would have asked the photographer

to take me to the buffalo stone on the edge of the coulee

on the farm where my mother grew up.

Once I would have asked her to take my picture

in front of the big lilacs that bordered the steps

that led to our first house in town,

but they’ve been torn out, replaced by a hedge

that has no blossoms, no smell.

Like the oils of the Old Masters, the photographs

are layered,

one image on top of another,

pentimento, something hidden underneath.

If you could peel away the thin surface

you’d find what the photographer started with,

the bare face of her seeing—

her features blurred—it leaves you dumbstruck, disquieted—

too much light pouring from her eyes.

In every village there are gardens or plots of weeds

where gardens used to be.

In every village there are prayers for the dead.

Cemeteries and brief narratives carved in stone.

Here numbers carry more meaning than words.

The summer days were long, they still are.

Winter scraped the first layer of skin

from a face. It still does.

A man and a woman reached for each other

in darkness or in the flare of mid-afternoon.

They still do.

The fire continues to move with the wind,

with the breath,

across the sheets.

What is it a fire sees? What does it make of the past,

the ashes it grows out of, the first flicker of memory

of heat and light?

Some women, away from the eyes of midwives and men,

licked their newborns like cats. Some licked the sweat

on their husbands’ bellies. Some chewed

kernels of wheat, touched the sweetness of

caragana stamens with the tips of tongues.

It was yesterday and tomorrow.

The windmill turned and turned,

water pouring into the trough, into the dugout,

the big animals gathering.

“Thankfulness.”

For the photograph, Olessa didn’t choose the Watson Hotel

where, in the early mornings,

she and her sister scrubbed away the evenings’ sins.

My mother wouldn’t have chosen

the farm where she grew up.

At 88, she’d have stood in front of the camera

in her Swift Current garden, mid-July,

among the pea vines, potatoes to either side,

enough to get her through the winter,

though she wouldn’t live to see that winter come.

There was rain and there was no rain.

Wood stoves, hot all over, burned arms and hips;

the scars remained, pits in the face from smallpox,

cuts from mower blades and butcher knives

when the pigs were slaughtered.

The cream separator became a planter, the coal oil lamps

novelties in a musty store. The word “pioneer” vanished

with the draft horses, the family bibles, the threshing crews.

Few were held back from school.

Whole towns died. Whole towns moved away.

Who is looking out the window now?

Who takes a picture of the picture taker?

Where are the buffalo that circled

the buffalo stone, scratching their matted backs?

I won’t pose there now. The grandchildren of my aunt

who stayed on the farm

painted her name on the granite. In the wallow

they planted plastic lilies and propped against the stone

three troll dolls with flaming hair.

Sorrow has entered the pictures.

Sometimes it’s in the face, sometimes

it’s in something as inconsequential

as a bottle of lotion by the bathroom sink.

If the camera captures souls

what about the animals who once lived in the village,

who worked on the farm? The horses named Dolly and Bill,

the black-and-white collies, the barn cats. When you look closely

at the long grass caught in the lens, do you glimpse a tail,

the tall grass hallucinating hooves and paws,

sending out to those who cannot see

the afterglow of the nowhere-to-be-found,

the once beloved,

passing through.

The photographer at ninety

begins to compose her self-portrait. She wants

the camera to pull her into the gravity

of her whole and only being.

She must use a timer, she must move quickly.

There must be nothing in her way; there must be everything.

It is her own eye she stares into. It must be empty enough

to take what it’s been given—grief, amazement,

the invisible, astonishing breath…

The wind puts its lips to Olesa’s harmonica,

composes an oratorio for old women,

for the boarded-up

hardware store, the blacksmith’s, the village hotel,

for the vacant lot where the garage used to be.

Everything the wind speaks to

answers back.

What happens to a life?

Where are the grass seeds blown from an old woman’s hand

over twenty years ago?

Where, after all, do you want your picture taken?

You must tell me now.